WATER + JellyFish = Marine MATH

Christina Hamlet

When describing her time at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, alumna Christina Hamlet uses the word "interdisciplinary" often. That, and "jellyfish."

Hamlet, a Kentucky native who earned her Ph.D. in Mathematics in 2011 at Carolina, connected with a cohort of people from many disciplines—including mathematics, mechanical engineering, chemistry, biomedical engineering and environmental sciences—while she completed her doctoral degree. Together, they examined the way a specific species of jellyfish interacts with the water around it. Broadly, research like this is known as fluid structure interaction.

"Imagine something with a soft body, like a jellyfish, pushing on fluid. The fluid can also push back on it," explains Hamlet. "When you're trying to figure out how something moves through the water, you can't just look at how it twists its body and moves."

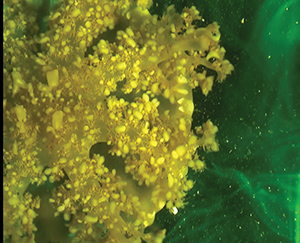

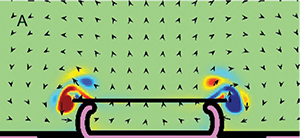

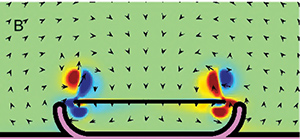

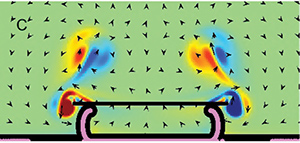

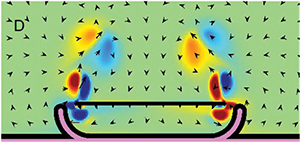

Hamlet and the diverse group of researchers worked with Laura Miller, professor in the UNC-Chapel Hill Department of Mathematics. They studied the Cassiopea, or "upside-down," jellyfish, Hamlet says. In particular, Hamlet performed numerical simulations, wherein a computer would solve equations related to the jellyfish's motion. Using this information, researchers could graph or animate the results.

Hamlet's study at Carolina was funded in many ways, including an interdisciplinary fellowship, research grants and teaching assistantships. And while Hamlet wanted teaching experience, she greatly appreciated the diversity of funding opportunities that allowed her to occasionally take a break from teaching and focus solely on her research. "It freed me from being tied to a teaching schedule all the time," she says. "As a result, I could collaborate and network. When you're doing interdisciplinary and collaborative work, being able to travel, talk to people and network becomes that much more important."

The Cassiopea jellyfish provided an interesting subject of this research. While this jellyfish can swim, it generally sits along the bottom of a body of water and pulses the water so food comes to it rather than moving to feed. The group believed this would be an opportunity to examine how this organism draws fluid to it, uptakes particles and dispels waste particles all while remaining stationary.

"It's just sitting there," Hamlet muses. "It's kind of a boring jellyfish in an exciting way."

Christina Hamlet observed a Cassiopea jellyfish (top photo) to create simulations of its movement (bottom images). Courtesy of Laura Miller

The lab where the research took place enabled the group to do their own "wetwork." In other words, they actually had a jellyfish in-house, a rare situation.

"One of the issues when you do interdisciplinary work is finding a collaborator that has the data you need to explore specific questions you are interested in," Hamlet explains. "If you are a mathematician who doesn't do experiments, you have to either find data in past writings that you can use or find a collaborator that is willing to gather the data for you. Having the jellyfish in the lab allowed us to design experiments that integrated well with our mathematical models."

How does this research apply outside the lab? For one, jellyfish have been studied as inspiration for underwater vehicle design, Hamlet explains. And the movement of underwater creatures led to the design for one of the machines that was recently used to swim through and filter water after the BP oil spill.

Hamlet's time since Carolina has also been promising. She currently is a post-doctoral research associate in the lab of Lisa Fauci, the associate director of the Center for Computational Science at Tulane University and Eric Tytell, co-PI and UNC-Chapel Hill alumnus. The ongoing project that Hamlet has joined examines how lampreys swim. As lampreys are one of the simplest vertebrates, Hamlet says, results can help researchers learn more about other vertebrates as well. She's currently working to build a comprehensive model showing how the creatures undulate through the water. In the future, however, she sees herself returning to her research roots.

"I'd like to gain a bit more experience doing integrated models and then eventually return to mathematical models of jellyfish—and also sea anemones—because there's a lot we can learn from them, especially how they do complicated motions using pretty small muscles," Hamlet says. It seems the Cassiopea jellyfish don't only send pulses through the water to attract food—they've also attracted the interest of one Chapel Hill alumna.

♦ Laura Lacy

Photo by Judi Bottoni

Special thanks to the Audobon Aquarium of the Americas